Why China Is Falling Out With Australia (and Allies)

What’s the China-Australia spat about?

(Bloomberg) --

China and Australia have become embroiled in a deepening political spat that is spilling over into trade. Even with some Chinese cities suffering power blackouts in December, the Beijing authorities continued to block coal shipments from Australia, underlining their determination. Miners aren’t the only exporters Down Under finding it harder to access their biggest market as tensions ramp up, nor is Australia alone in feeling heat. Other countries that have clashed with China, including Canada, the U.K. and India, have joined Australia in boosting cooperation and intelligence sharing, while the incoming U.S. president has promised a more united front against Beijing.

1. What’s the China-Australia spat about?

Ties have been on a downward spiral since 2018 when Australia, accusing China of meddling in its domestic affairs, passed a new law against foreign interference and espionage. It also barred Huawei Technologies Co. from building the country’s 5G mobile network, among the first countries to do so, citing national security. The atmosphere worsened in April after Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government called for an international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus that causes Covid-19. Then in November a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman tweeted an edited image of an Australian soldier holding a knife to the throat of an Afghan child -- a barbed reference to an ongoing war crimes probe. At a time when Chinese “wolf warrior” diplomats are getting increasingly combative, Morrison’s demand for an apology was rebuffed.

2. What’s the economic impact been?

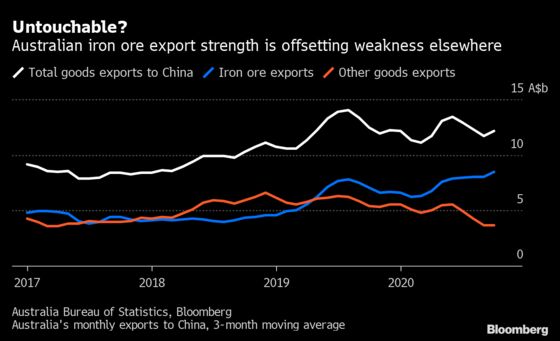

Considering China is Australia’s top trading partner by far, the impact has been relatively small -- although the individual sectors hit would beg to differ. Starting in May, China slapped crippling tariffs on Australian barley; banned beef from four major meat processors; launched an anti-dumping probe into Aussie wine that led to massive levies; and told importers to stop buying cotton and lobsters. Timber exports were banned and at least $500 million of coal delayed for months off Chinese ports -- apparently one of the catalysts for the blackouts. Still, while the reprisals have generated myriad headlines and spurred some exporters to call on Morrison to back down, the combined impact as of January amounted to a loss of just 0.3% of Australian gross domestic product, or A$6 billion ($4.7 billion), according to government figures. Sales of iron ore, the nation’s largest cash cow, are still booming.

3. Why is China doing this?

After months of obfuscation, the Chinese embassy in November issued a list of 14 grievances. They included Australian decisions to reject Chinese investment on national security grounds, providing funding to what it sees as an anti-China think tank, and “incessant wanton interference” in Chinese affairs regarding Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and in the South China Sea. It also cited allegations of racist attacks against Chinese people and accused the nation’s independent media of being antagonistic. But state-backed scholars in China have said what’s most angered authorities in Beijing is Morrison’s push for independent investigators to be allowed into Wuhan, which they see as a slight against Chinese sovereignty, as well as his government’s willingness to echo and coordinate with U.S. President Donald Trump’s anti-China campaign. “Frankly speaking, we have heard too many negative voices and seen various negative moves from the Australian side,” Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in December. President Xi Jinping’s government has a record of using trade as a cudgel, with South Korea, Japan and Taiwan all experiencing reprisals in recent years.

4. Is there a way out for Australia?

It’s not obvious. Chinese diplomats and state media have said it’s up to the government in Canberra to reset ties, but they haven’t publicly made clear what Australian moves would be enough to reverse the trade reprisals. Chen Hong, director of the Australian studies center at East China Normal University in Shanghai, said China is unlikely to back down until it sees substantial actions, not just rhetoric. Morrison has indicated he’s unwilling to act on any of the 14 grievances; he and his ministers seem to be waiting for China to lower the temperature so a new “settling point” in the relationship can be found. Meanwhile, at year-end Australia said it would formally challenge China at the World Trade Organization.

5. Is Australia the only country targeted?

Increasingly, no. The U.K. has been the subject of rising vitriol, particularly over its support for Hong Kong’s autonomy. Canada’s insistence that any free-trade deal talks with China needs to address human rights seems to have scuppered a potential pact. Things soured further with Canada’s arrest in 2018 of a top executive at Huawei Technologies Co. in Vancouver on a U.S. extradition request. China locked up two Canadians and halted billions of dollars in agricultural imports in the months that followed. Tensions between India and China have been escalating since their soldiers began clashing along the Himalayan frontier in 2019. India has banned dozens of Chinese apps, citing national security.

6. Are they helping each other?

Morrison has been openly reaching out to what he calls “like-minded countries” to form a unified front against what his government considers Chinese aggression. That’s meant an increase in ministerial-level meetings of the Five Eyes intelligence sharing network that also includes the U.S., U.K., Canada and New Zealand. The long-moribund Quad -- a security framework with the U.S., Japan and India -- has been revived and in November held naval exercises in the Indian Ocean.

7. Will Joe Biden change things?

China sees the Trump administration’s policies, such as its trade war, as so extreme that they bordered on reckless. Party officials in Beijing think those policies are unlikely to remain under the new U.S. president, who’s viewed as more traditional. That could then lead Australia, as a close U.S. ally, to dial down what China sees as hostility triggered by anti-communist ideology. Still, there is strong bipartisan support in Washington for a tough line on China. Biden was vice president during Barack Obama’s geopolitical “pivot to Asia,” which sought to counter China’s growing influence in the region, and his support for multilateralism could promote an even more united front against Beijing.

The Reference Shelf

- More QuickTakes on China’s wolf warrior diplomats, U.S.-China flashpoints, the fight over Huawei and the Biden agenda.

- In-depth looks at disputes in the South China and East China seas.

- Businessweek on what happened to the relationship between China and the U.K.

- A Bloomberg storythread shows the price Australia is paying.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Shuli Ren lays out China’s three biggest mistakes in 2020.

- Quartz profiles a Chinese wolf warrior cartoonist.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.