The Race for 650 Million Virtual Bank Accounts

Competition is heating up for Southeast Asia’s digital-savvy customers. But some brick-and-mortar lenders are sitting pretty.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s tech giants have upended the country's payments system and promise to shake up its consumer-banking sector. The rest of the region won't be so easy.

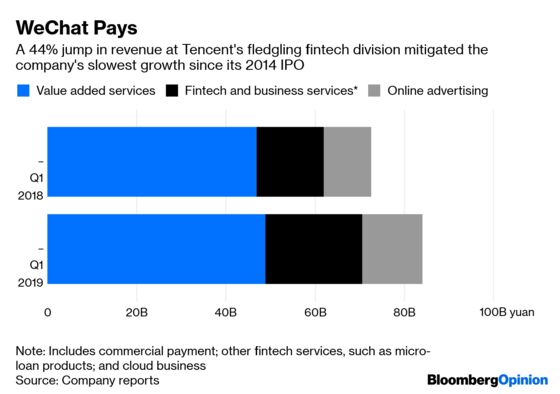

Asia is quickly becoming the next battlefront for Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.'s Ant Financial and Tencent Holdings Ltd.'s WeChat Pay, after both secured licenses to set up online-only banks in Hong Kong earlier this month. Singapore’s welcoming regulatory environment makes the city-state an obvious entry point to Southeast Asia.

The region’s huge market could offer some easy wins. Much of its population of over 650 million are digitally savvy smartphone owners, already comfortable with ride-hailing apps like Go-Jek and Grab. Meanwhile, inefficient bank branches, low interest rates and poor professional investment advice is trumping privacy concerns: 62% of people in developing Asian countries don’t mind sharing personal data to get customized products, compared with just 23% in wealthier Asian nations, according to a 2017 survey by McKinsey & Co.

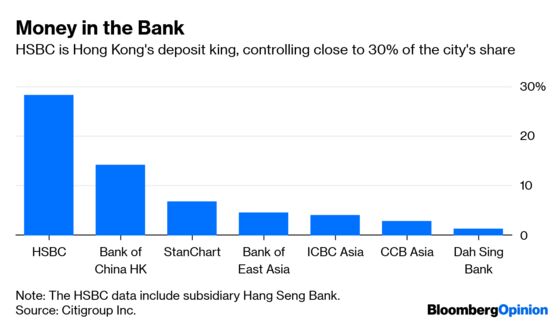

Yet traditional lenders remain formidable competitors. Take Hong Kong: While the city has awarded licenses to eight virtual banks, three have gone to incumbent lenders Standard Chartered Plc, BOC Hong Kong (Holdings) Ltd. and Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. HSBC Holdings Plc, which has a lock on nearly 30% of the city’s deposits, hasn’t even applied.

HSBC may have good reason to be unmoved. Together, the city’s virtual-bank contenders will have a balance sheet of just HK$150 billion ($19 billion), which would put them on par with Hong Kong’s third-smallest bank, Dah Sing Banking Group Ltd., according to Citigroup Inc. While picking up retail customers is one thing, getting them to put large amounts of money into a virtual bank account is another. Without a big-name lender behind them, newcomers grapple with a trust deficit.

Virtual banks also aren’t exempt from frustrating know-your-customer routines, which can hinder efforts to sign up cash-heavy small and medium enterprises. A hair salon that finally convinced HSBC it’s not laundering money will be reluctant to repeat that process. While an individual can open a virtual account in a matter of hours, the same can’t be said for SMEs, which face more onerous regulatory hurdles. That means it’s unlikely to be any less time-consuming than the average 38 days it takes for a traditional bank in Hong Kong. (As tedious as they may seem, such rules could help virtual banks avert some of the costly regulatory blunders of their rivals – particularly given startups often lack deep expertise in operational risk management.)

Another issue is that newcomers’ cost advantages may be smaller than anticipated. Virtual banks might save money by not having branches, but Hong Kong is setting the same capital requirements for online-only banks as their bricks-and-mortar rivals – something Singapore is likely to replicate.

Then there’s liquidity. Singapore’s DBS Group Holdings Ltd., which started a mobile-only digital bank in India in 2016, claims to be targeting SMEs with data-driven lending. It’s unclear if the deposit base required for a meaningful operation can come entirely from online-only customers. In Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam – in addition to China and India – 46% of consumers flatly refused to move any of their money to a bank without branches, according to the 2017 McKinsey survey.

That doesn't mean traditional banks should get complacent. Many startups are backed by deep-pocketed Chinese tech giants, which gives them the flexibility to scale up quickly. Old-world banks may be able to capitalize on this by developing more alliances with them. Using Chinese partner ZhongAn Online P&C Insurance Co.’s technology, for example, Tencent-funded Grab Holdings Inc. is offering its ride-hailing app in Singapore as a platform for insurers to sell policies without agents or brokers. About 60% of Citigroup’s consumer credit cards in Asia are now paid via Ant’s Alipay, according to the bank. Paytm, India’s most popular digital payment service, has made its peace with plastic: It’s now issuing credit cards jointly with Citi.

Ultimately, big banks may even want to consider ceding some of this race for retail clients to nimbler tech rivals. The real money to be made is in a dustier corner of the banking business: in the accounting departments of large multinationals. We’ll explore this option in a second column.

Eight virtual banks have won licenses, with Chinese players partnering up with incumbents or local companies in all but one case. These include: Hong Kong fintech firm WeLab Holdings Ltd., Ant Financial, Tencent, smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp., JD.com Inc., Ping An Insurance Group Co.'s OneConnect, travel site Ctrip.com InternationalLtd., ,ZhongAn Online P&C Insurance Co.

Citi's estimate assumes each licensee will bring in roughly HK$1.9 billion in capital and leverage it 10 times.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nisha Gopalan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and banking. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones as an editor and a reporter.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.