The Extraordinary Journey of Your Mother’s Day Flowers

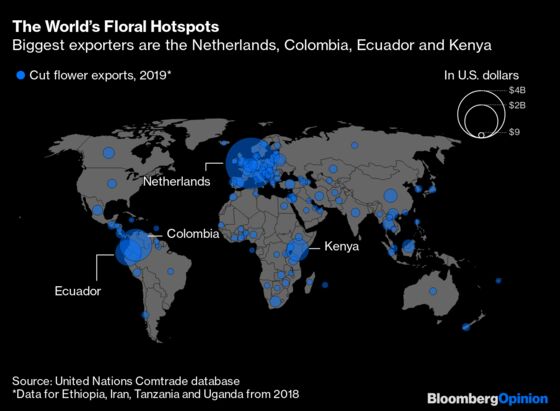

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since the tulip mania of the 1600s, the Netherlands has developed into the hub of the global flower trade, not only growing huge quantities of tulips, roses and other flowers but also importing, auctioning off and re-exporting flowers grown elsewhere. It’s the big blue circle in the upper middle of the map below, with $4.3 billion in 2019 cut-flower exports — about half the global total.

When a colleague asked me a few weeks ago to answer the pressing question of where all the Mother’s Day (and Valentine’s Day, and Easter, and Administrative Professional and Secretaries Day, and National Teachers’ Day, and so on) flowers come from, I thus figured it would end up involving a giant flower auction house in the Netherlands.

But no. For one thing, Dutch growers’ cooperative Royal FloraHolland has been moving away from live auctions to mostly digital trading, a process accelerated by the pandemic. More to the point, apart from tulips and unique varieties destined for high-end displays at weddings and such, we here in the U.S. generally don’t get our flowers from the Netherlands.

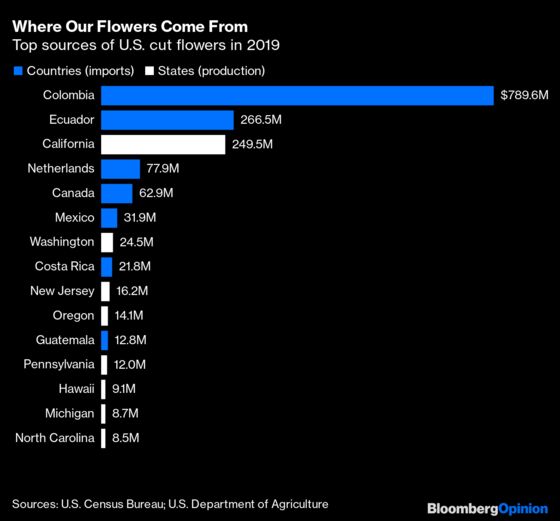

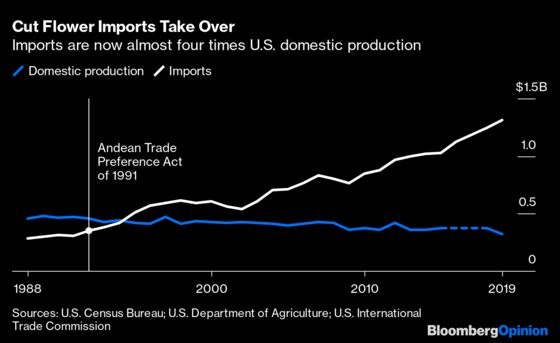

The U.S. is the world’s biggest importer of cut flowers, at $1.6 billion in 2019, dwarfing the either $386 million or $326 million in sales by domestic growers, depending on which U.S. Department of Agriculture survey you look at. The hub of our flower trade is not a Dutch auction house or even a digital trading platform, but Miami International Airport, through which about 80% of those imports flow. They arrive there from several different countries in Central and South America, and from the Netherlands too. But mainly they’re from Colombia.

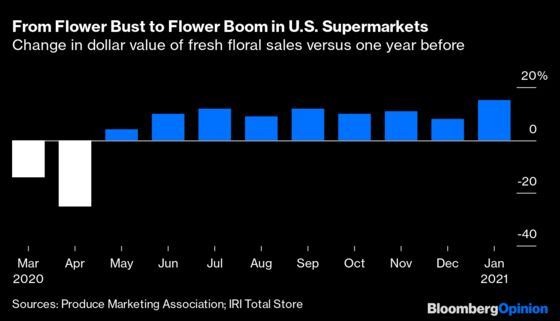

The numbers in the above charts are from 2019 because so far there’s only incomplete data on global exports and no data on state production from 2020. But 2020 was an interesting year for flowers! Last spring — right in the middle of the Valentine’s-to-Mother’s-Day high season — the coronavirus pandemic shut down large parts of the global economy, not to mention churches, weddings and other big sources of flower demand. “In mid-March, it even seemed as if the floriculture industry might collapse,” Royal FloraHolland Chief Executive Officer Steven van Schilfgaarde wrote in the cooperative’s recently released 2020 annual report.

Instead, Royal FloraHolland ended up reporting a modest pre-tax loss of 6.8 million Euros ($8.2 million) for the year. In the U.S., some parts of the flower business actually had a great 2020, with 2021 looking even better. Supermarket flower sales, for example, rebounded quickly and as of January were running 15% higher than a year before.

Revenue also rose 67% in 2020 for the consumer floral division at 1-800-Flowers.com Inc. (which also sells fruit baskets, services to florists and other things), while multiple Society of American Florists member surveys in recent months have reported big holiday sales increases over past years. Amid a pandemic, “people are realizing that time is of the essence,” one florist recently told the New York Times in explaining the surge. “You can’t hold a grudge.”

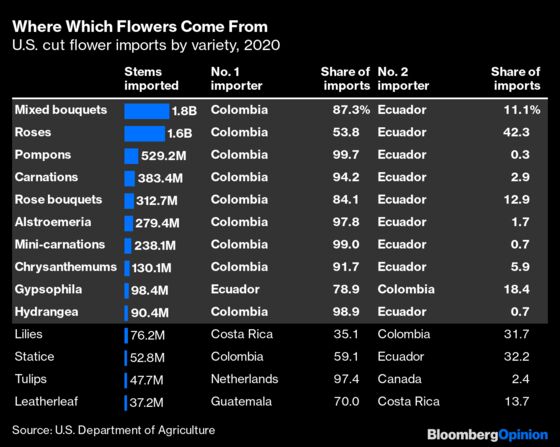

Not every part of the business has boomed. Data on 2020 U.S. cut-flower imports are available, and they declined by $47 million, or 3.6% (5.4% if you go by the number of stems imported) versus 2019. The dollar-value of imports from the Netherlands — again, the source of many flowers for weddings and other events — fell 41%. But imports from Colombia rose 3.4%.

How did Colombian flowers come to so dominate the U.S. market? One origin story begins with Colombian businessman and gardener Edgar Wells Castillo’s visit to a wholesale flower market in New York in the early 1960s — or maybe it was a florist’s shop in Washington. Upon seeing the prices charged there he sensed a business opportunity, subsequently putting his first shipment of carnations and chrysanthemums on a jet to Miami in October 1965. Another story credits grower Francisco Waldorf with starting the commercial cultivation of carnations on the Bogota savanna a year before that.

Other versions put more emphasis on a 1966 U.S. Agency for International Development agricultural mission to Colombia and the 1967 paper by Colorado State University horticulture graduate student David Cheever (who may have been on that mission; he died in 2013 so I can’t ask him) that seems to have done the most to alert people in the U.S. to the attractions of growing flowers at 8,700 feet above sea level near the equator. Cheever’s paper described how the Bogota savanna offered, as paraphrased in Smithsonian Magazine a few years ago, “a pleasant climate with little temperature variation and consistent light, about 12 hours per day year-round — ideal for a crop that must always be available.” The soil was also great, and prevailing wages at the time were about 5% of those in U.S. horticulture.

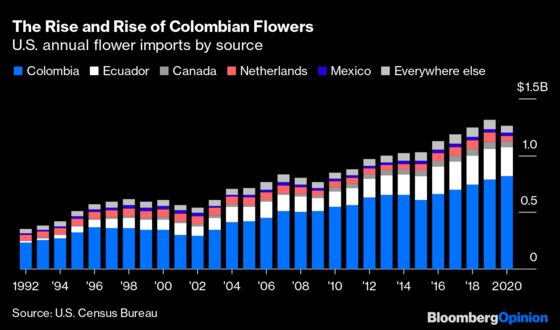

The company that Cheever and three other Americans founded in 1969, Floramerica, became for a time the dominant player in Colombian flower exports. Cheever soon quit to work as independent consultant, though, helping lots of others get into the business. The value of Colombian flower exports to the U.S. rose from $4,000 in 1965 to $765,000 in 1970 to $30 million in 1977. That year the the Growers’ Division of the Society of American Florists petitioned the U.S. International Trade Commission to look into whether these imports were harming U.S. growers, but the ITC concluded that they were “not being imported into the United States in such increased quantities as to be a substantial cause of serious injury.” Then, as the exports kept growing through the 1980s — which is when Ecuador, which offered high-altitude equatorial growth conditions similar to Colombia’s, started exporting flowers as well — other considerations came to weigh heavier with policy makers in Washington than the interests of U.S. flower growers.

Those considerations were encouraging political stability and discouraging illicit drug cultivation in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, and in 1991 President George H.W. Bush signed into law the Andes Trade Preference Act, which offered duty-free treatment to certain products from the region, among them flowers. The most recent version of the Andes trade pact expired in 2013, but Colombian flowers continue to enter the U.S. duty-free, while those from Ecuador face modest tariffs. Cut flowers were the No. 5 export by value in 2019 for both countries, according to the United Nations’ Comtrade database, behind oil, coal, coffee and gold in Colombia and behind oil, frozen shrimp, bananas and canned tuna in Ecuador.

The rise of the South American flower industry has not exactly ended the illegal-drugs trade, with Colombia reportedly growing more coca than ever and Ecuador becoming a major transit route for cocaine. It has also attracted much criticism over lax labor standards and environmental misdeeds, although some of those concerns seem to have been addressed at least partially in recent years. On the positive side, the industry’s rise has coincided with relatively good economic times in both countries — after oil-related busts in the late 1990s, both have outperformed the rest of Latin America economically since 2000, with Colombia’s per-capita gross domestic product growing at twice the region’s overall rate. And it’s been good news for U.S. consumers. Since 1993, the prices of indoor plants and flowers have risen at less than a third the rate of overall inflation, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and that’s after a sharp price runup during the post-lockdown flower boom.

It’s harder to put a positive spin on the ramifications for U.S. cut-flower growers. Cut flower imports first surpassed domestic production four years after the 1991 trade pact, and the gap has only grown since. I didn’t adjust these numbers for inflation because there doesn’t seem to have been much flower-price inflation, but the true trajectory of the domestic industry is probably even more negative than it appears in the chart.

The U.S. flower business was being turned upside-down even before the import boom, though. The industry had first taken shape in the decades after the Civil War as florists built greenhouses to serve nearby urban markets. When the Census Bureau took its first detailed look at commercial floriculture for the 1890 agricultural census, New York was the clear No. 1 in growing cut flowers for sale, followed by Illinois, Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The greenhouses ranged in size from 150,000 square feet to 60, “the latter a cozy attachment to the sitting room of a New England farmhouse, whose mistress sells annually $35 to $50 worth of plants and flowers.” Roses and carnations were the top crops, accounting for about 65% of what the Census Bureau calculated with remarkable precision to be a national total of $14,175,328.01 in cut-flower sales.

Adjusted for consumer-price inflation by MeasuringWorth.com, that amounts to $426.5 million today, or well more than the domestic industry now generates. As a share of GDP it’s equivalent to almost $20 billion, or about ten times the combined value of imports and domestic production today. Either cut flowers have become much less important to Americans than they were in 1890, or there’s been a floral productivity revolution. I think it’s mostly the latter.

That revolution seems to have begun in and around Denver, where sunny skies, Platte River water and ample local supplies of coal and natural gas to heat greenhouses spurred a “Carnation Gold Rush” that began in the 1890s and culminated in Colorado becoming one of the world’s top producers of the long-lasting, easy-to-transport flower. California and Florida, where long growing seasons allowed for large-scale flower production outside of greenhouses, also began shipping flowers farther and farther afield as the 20th century progressed. The short lifespan of most cut flowers still kept the greenhouses close to big cities alive, if not exactly booming, but after the advent of jet transportation in the late 1950s the old business model finally imploded. “We were a predator group — wiping out the industry in the rest of the United States,” one Denver flower wholesaler recalled in a remarkable 1996 retrospective in the alternative weekly Westword.

Big, specialist growers that shipped their products long distances were taking over the flower business. But the industry’s evolution didn’t stop along Colorado’s Front Range. Local growers funded research at Colorado State University into ways to become even more productive, leading to the paper by David Cheever that spelled their demise. “The argument had been: Colorado or California,” a Colorado Springs grower told Westword. “Unfortunately, the answer they came up with was Colombia.” It didn’t help that, just as the Colombian export business was getting going in the 1970s, the energy crisis made heating greenhouses through the Colorado winter much more expensive.

Colombia now grows more than 90% of the carnations sold in the U.S., and more than half of the roses. Those two flowers and pompons, a kind of chrysanthemum, are the top U.S. flower imports from South America. You have to get down to the No. 11 import by volume, lilies, to find a market not dominated by Colombia and Ecuador.

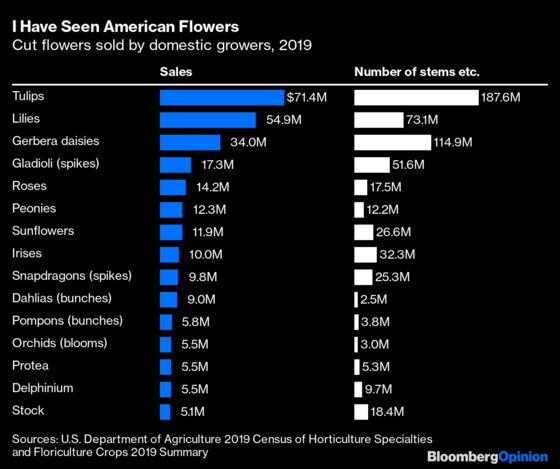

What does this leave for American flower growers? Well, mainly growing flowers intended for planting rather than putting in vases, which because they come attached to lots of soil don’t really pay to be flown in from another continent. U.S. commercial floriculture enterprises generated $4.4 billion in sales in 2019. Cut flowers, once the mainstay, now take a backseat to flats of pansies and petunias and pots of begonias and geraniums.

Domestic producers also still grow the kinds of cut flowers that can’t easily survive a couple of airplane flights and a long stay in a supermarket produce section. These are the prettiest flowers, in my opinion, if not necessarily the most profitable. (The chart headline is a lyric from this song.)

I would have liked to list the main states where these flowers are grown, as I did with imports and countries. But while the USDA can tell you exactly how many flowers of which variety from which country land at the Miami airport every day, it’s much cagier about disclosing where some flowers are grown domestically, because doing so might divulge proprietary information about certain large growers.

For example, the country’s most famous tulip-producing region is Washington’s Skagit Valley, just north of Seattle, but the state accounted for only 20% of 2019 U.S. tulip production by sales volume and the USDA doesn’t disclose significant totals for any other state. Bloomia, founded in 2004 by a transplanted Dutch tulip farmer, says it grows 75 million tulips a year, 40% of the national total, in its hydroponic greenhouse complex near Fredericksburg, Virginia, so maybe Virginia is tops for tulips. California is definitely No. 1 for lilies, gerbera daisies and roses, growing more than 90% of U.S. production of each. The source of the nation’s gladioli is a mystery as far as the USDA is concerned, but Great Lakes Glads of Bronson, Michigan says it’s the top producer. Oregon appears to lead the way in peonies, California and New Jersey in sunflowers. And so on.

So where do all the Mother’s Day flowers come from? In most cases they’re grown in Colombia. But the more creative you get about assembling the bouquet, the more likely you are to encounter blooms from elsewhere.

The U.S. also exports some of the flowers it grows and the USDA’s domestic production numbers miss out on the smallest growers, but for purposes of my chart those more or less cancel each other out.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.