The Countries That Pay in the IEA’s Path to Net Zero Emissions

International oil majors are already turning their attention away from costly and uncertain deepwater exploration and development

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Last week the International Energy Agency laid out a pathway for reaching net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. One feature got a lot of attention: It called for an end to oil exploration and the development of new fields.

The agency is not arguing that the oil industry should be prevented from looking for and developing new assets; rather, it’s saying that the fall in demand that is needed to reach the net zero goal will make such prospecting unnecessary. Still, a mass reduction in oil exploration will make things extremely difficult for countries that have relied on international companies investing billions of dollars to find and develop their oil.

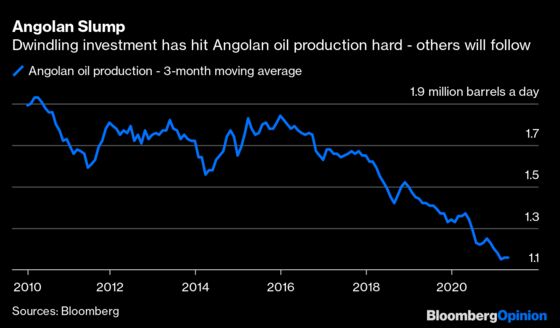

Angola is a case in point. Its oil production has been in steady decline since 2016 and that’s only going to accelerate.

The country relies on foreign oil companies to extract crude from fields thousands of meters below the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The 2014 oil price crash hit investment in its oil sector hard and production began to fall two years later, when the flow of projects that were already in development came to an end. Crude production fell by a third in little more than four years.

Steep declines at Angola’s offshore fields mean that, without investment in exploration and the development of new deposits, its production will fall further. Other West African countries — Nigeria, the continent's biggest oil producer, among them — will suffer a similar fate.

International oil majors are already turning their attention away from costly and uncertain deepwater exploration and development, which only yields income after years of work and billions of dollars of investment. For example, the first fields in what became BP Plc’s Greater Plutonio project were discovered in mid-1999, but didn’t yield their first commercial barrels of crude for more than eight years. Instead, companies are turning toward the quick returns from smaller investments available in the U.S. shale patch.

Royal Dutch Shell Plc has also decided that its onshore production in Nigeria is not compatible with plans to go green. And BP and ENI SpA are considering merging their Angolan assets into a joint venture in a bid to revive output.

As production from these countries declines, two major trends will emerge.

First, the world will become increasingly dependent on fewer countries for the dwindling volumes of oil it still consumes, which will concentrate power in the hands of producers in the Middle East, Russia and North America.

Second, the average barrel produced will become heavier (containing a higher proportion of large hydrocarbon molecules that must be cracked to produce the fuels consumers want) and more sour (containing higher concentrations of sulfur that must be removed). This will put pressure on older refineries in Europe and the U.S. that can’t extract the same value from this type of oil as more modern plants.

We are already seeing big new refineries being built in the Middle East and Asia to process heavy, sour Persian Gulf crudes, as older plants elsewhere closing or become storage terminals or biofuels producers. This process will accelerate as oil demand peaks and then starts to fall.

And what about oil prices? That will depend on the relative speed of the declines in oil demand and supply.

If the path to net zero is dominated by falling oil demand, oil prices will weaken as producers struggle to respond to a declining market — much as they did when the pandemic hit demand last year, but in a more drawn out and less dramatic fashion. If oil demand proves more resilient, however, while investment in the industry dwindles, prices will likely rise, albeit probably only briefly. But by then it may already be too late for producers like Angola.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.