The Transplant Waiting List Is Where Hope Goes to Die

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s illegal to pay for a human kidney, but it’s perfectly fine to beg for one. So if you’ve driven through Alabama, Indiana, South Carolina, Manhattan or Los Angeles recently, you may have seen billboards taken out by patients urging passers-by to part with their kidneys. Hundreds more patients seek living donors online; others search abroad (often with grim results).

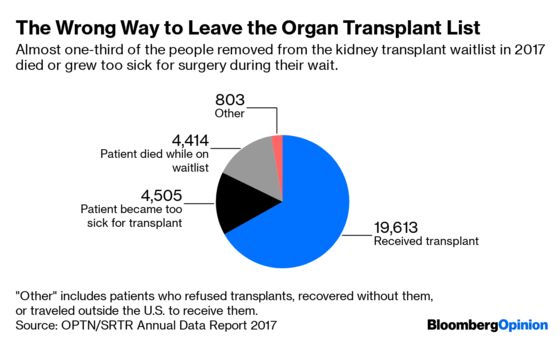

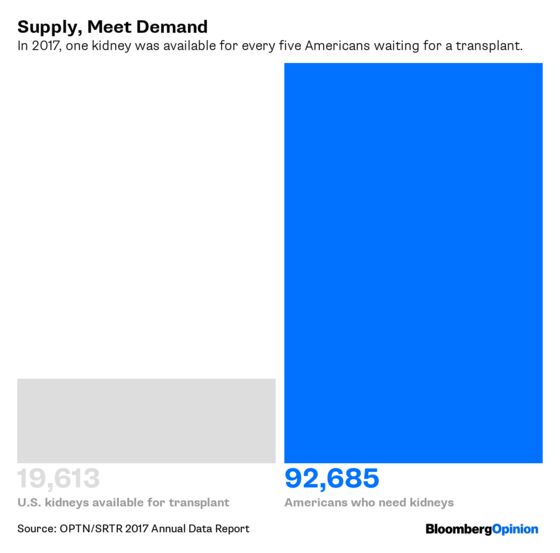

There just aren’t enough organs to go around. For every 1,000 Americans who pledge to donate their kidneys after death, only three die in a way that permits a transplant. That frees up about 14,000 kidneys a year — about one for every seven people on the 90,000-strong transplant waiting list. The longer they wait — five years, on average — the sicker they get. Every day, some 13 people die waiting.

That’s why living donors are so important — and why donations should be encouraged rather than penalized.

Roughly 6,000 Americans donate one of their kidneys each year, typically to a family member or friend. It’s hardly an easy decision. Complications are rare, and healthy donors generally don’t experience long-term problems — some evidence suggests they actually live longer than average. But all surgeries carry risks, and donors have to plan for a two- to six-week recovery period. This puts them at risk of being laid off. They might also find themselves denied health or life insurance. Donors should be protected from these costs not just to reward their generosity, but because their selflessness provides clear public benefits.

The gain to the recipient, of course, is obvious. With a kidney transplant, a patient can live a relatively normal life. Without it, he or she must spend an average of five to 10 years on dialysis — a costly, grueling process that often interferes with work and family — followed by an early death. Dialysis patients report lower quality of life and more complications than transplant patients. They are less independent and die sooner. There’s a reason doctors consider kidney transplants the treatment of choice. And patient outcomes tend to be best of all with living-donor kidneys.

But transplants aren’t just better for patients; they’re a better deal for taxpayers. A year of dialysis costs nearly three times as much as a transplant, and Medicare covers about 80% of dialysis costs for most patients. That’s an outlay of $35 billion each year. Every transplant saves taxpayers about $146,000 over the course of the recipient’s lifetime. Researchers estimate that if every American who needed a kidney could get one, it would save taxpayers $12 billion a year.

If everyone benefits from living donations, then the state should take action to encourage them — and indeed, many states are. Colorado, Idaho, Maine, Maryland and New York have all passed bills to encourage living organ donations and prevent donors from being discriminated against. And at the federal level, a bipartisan group of representatives in February introduced the Living Donor Protection Act, which would ensure donors can take up to three months off work to recover and would prohibit insurers from limiting coverage or charging higher premiums to live organ donors. These are good first steps.

Even bolder thinking may also be in order — for example, revisiting the 1984 law that bans payment for organs. If the government gave $45,000 to each living donor as “an expression of appreciation by society,” as some nephrologists have proposed, it would save up to 10,000 lives a year and taxpayers would still come out more than $10 billion ahead. Such a plan could end the kidney shortage at a stroke. The prospect of the impoverished in effect selling their organs is admittedly disturbing — but is it any more disturbing than the fact that, as things stand, the wealthier, whiter, and younger you are, the more likely you are to receive one of those rare living-donor kidneys?

Still, one step at a time. Before debating new incentives for organ donation, at least take down the disincentives already in place. Nobody should lose a job or be denied health insurance for saving a life.

In 1972, Congress extended Medicaid eligibility to the vast majority of Americans with chronic kidney disease, regardless of their age or ability to pay. One analyst described the entitlement as “the first (and perhaps last) designed to cover a particular diagnosis.”

Editorials are written by the Bloomberg Opinion editorial board.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.