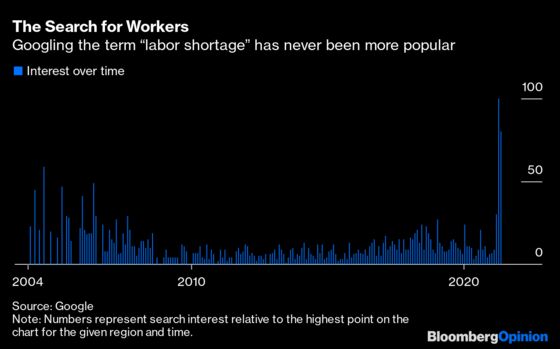

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The job market is finally showing some convincing signs of recovery, with the quickest pace of hiring in 10 months recorded in June. Yet that’s done little to alleviate recent concerns about whether the U.S. has enough workers. The term “labor shortage” was Googled more in May than at any other point in the search engine’s history going back to 2004. Headline after headline has cited wage rises, bonuses and other perks that seem to make it a job hunter’s market.

The concept sounds simple — American companies must be struggling to find the employees they need. Yet some labor economists would argue that the picture isn’t complete. Employers are unable to find the workers they want at the wages they’re willing to pay. Failing to appreciate this distinction could lead to policy errors down the road. It’s just one of many popular misconceptions that distort the lens through which U.S. politicians and policy makers view the labor market, with negative consequences for both workers and employers.

In capitalist markets, the laws of supply and demand should make spotting labor shortages relatively straightforward. When there aren’t enough workers, employers pay more to get them and wages go up. This dynamic is playing out in real time for hourly employees at companies such as McDonald’s Corp. and Amazon.com Inc., which is offering $1,000 signing bonuses and raising average hourly pay in some locations. Competitors eager to retain talent are thus compelled to boost their wages — not only for newly hired employees but existing ones, too, who start to demand more.

Yet quickening wage growth isn’t the only hallmark of a shortage. The telltale sign is seeing this trend alongside stalling job growth, as Heidi Shierholz, senior economist and policy director at the Economic Policy Institute puts it. Just look at what’s been happening in the leisure and hospitality sector, among the most bruised by the Covid-19 shutdown. After jobs all but vanished in the throes of the pandemic, we’re starting to see a rebound: In June, the sector created 343,000 jobs, far outpacing other corners of the economy and contributing heavily to the overall increase in nonfarm payrolls of 850,000. Meanwhile, average weekly earnings have been rising faster than many other industries. In other words, the market is working to resolve a shortage: When employers lift wages, they’re able to attract the employees they need, as Shierholz said in a recent podcast. (She also notes that leisure and hospitality wages are only just meeting pre-Covid levels; they are not too high.)

To assess a shortage accurately, though, you need to look beyond industries to specific occupations and locations. In the past, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has used the taxicab queuing model, based on work by English statistician David George Kendall, to address the on-again, off-again debate about a shortage of workers in science, technology, engineering and math.

In the analogy, employers and job openings can be thought of as taxis, while workers are a line of waiting passengers. Depending on your location, there may be a long line of taxis (say, at the airport), or conversely a long line of passengers (at a hotel). Demand for petroleum engineers in Texas, for example, is different from petroleum engineers in Massachusetts, authors Yi Xue and Richard Larson note.

Then there may be different lines depending on whether you’re paying with cash or a credit card, or waiting for an Uber. Much in the same way, there are separate queues for each STEM occupation. Demand for employees with doctorates in mechanical engineering differs from demand for bachelor’s degree earners in the same field, the authors note, while the supply of workers with Ph.D.’s in biomedical sciences is distinct from the supply of those with doctorates in physics.

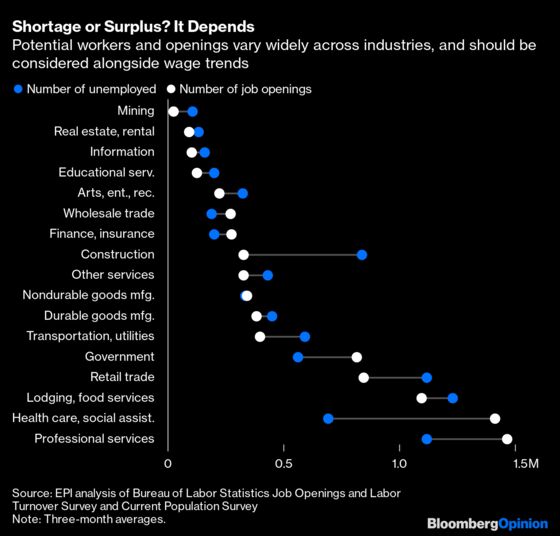

The bottom line is that, whether in STEM or other fields, shortages are not universal. Simultaneous shortages and surpluses can sprout up across the economy at any given point, which is why broad-brush policies can be counterproductive.

One standard response to a labor shortage is to expand the pool of foreign temporary workers, who can fill empty positions quickly. Last month, a bipartisan group of House members proposed a bill that would expand the H-2B visa for low-wage jobs, including hospitality, restaurants, seafood and meat processing, landscaping and construction. The same is happening for white-collar work: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has called to double the cap for H-1B visas, used primarily for tech employees. Yet unemployment rates in industries that overlap with the H-2B visa are still high; and lower-paid guest workers have helped suppress tech wages for years. Adding more workers could exacerbate both trends.

With immigration now firmly established as a wedge issue, sorting such policies from their consequences has become a hyper-politicized and impulse-driven process. There’s a better way. The U.K.’s Migration Advisory Committee, established in 2007, is an independent government agency that relies on a data-driven framework to answer three main questions when seeking to determine whether an occupation faces a shortage:

- Does the occupation require certain skills?

- Is there evidence of a shortage?

- Is it “sensible” to fill those shortages with migrant workers?

The MAC combines macro analysis, based on labor-market data such as wage growth and unemployment rates, with micro analysis, including reports from employers, trade unions and other sources. The closest the U.S. comes to anything like a shortage occupation list is the Labor Department’s “Schedule A.” It has just two occupations on it, neither of which have been reassessed in three decades. While MAC-like commissions are supported by bipartisan groups and think tanks, and have been proposed before by lawmakers — as part of a comprehensive immigration reform bill in 2009, and again when it was reintroduced in 2013 — legislation to create one has never progressed.

The MAC’s advice is public and non-binding: The government can choose to accept or reject its recommendations. Shortly after its inception, the committee examined shortage claims for caretakers of the elderly employed by local governments. The MAC was credited with fostering a better public conversation about wage levels and the role of migrant workers. In the end, wages rose, albeit too modestly to address some root problems, and the U.K. accepted more guest workers. The outcome may have been imperfect, but it reflected evidence-based debate and some degree of compromise.

Compare that with what happens in the U.S., where the conversation is largely driven by businesses trying to influence policy makers behind closed doors, write Daniel Costa of the Economic Policy Institute and Philip Martin, an economics professor at the University of California, Davis. “While the data are sometimes clear, in many cases, shortage determinations are an inexact and subjective science,” Costa wrote in an email. Without a credible source of information and set of objective criteria, we’re ceding the debate to the loudest lobbyists with the fattest wallets.

A shortage misdiagnosis can have serious repercussions, particularly if it leads to policies that offer up lower-cost substitutes for American workers and suppress wages. In the early 2000s, right after the dotcom bust, Congress raised the H-1B cap to 195,000 from 115,000 (and 65,000 in 1998) to placate demands of the tech industry. Unemployment in computer and mathematical occupations ended up rising steadily and wages flatlined. Absent a standard or scientific way to assess whether shortages exist, such errors will be repeated.

Independent commissions have their skeptics, but a formalized debate will be better than the supercharged guesswork we’re using now. The cost of miscalculation is too dear to rely on well-funded, self-interested hunches.

While unemployment rates for computer occupations have been generally falling over the past year, it’s important to compare those figures with other occupations that require a similar level of education, rather than the economy as a whole.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Rachel Rosenthal is an editor with Bloomberg Opinion. Previously, she was a markets reporter and editor at the Wall Street Journal in Hong Kong.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.