There’s a Hole at the Heart of Europe’s Gas Supply

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Europe has the gas. Whether that will cover all eventualities is a different, more anxious question.

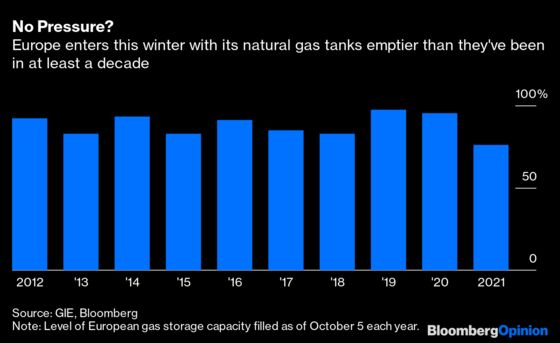

The continent’s natural gas storage facilities are 76% full. That is by far the lowest level at the beginning of heating season in the past decade.

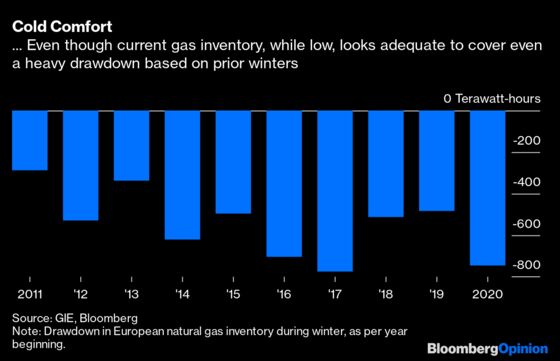

In absolute terms, though, is 76% so bad? It adds up to 841 terawatt-hours by GIE’s reckoning (about 2.8 trillion cubic feet). That is well below the five-year average, but that average has been skewed upward by unusually loose conditions in 2019 and 2020. The current level is only about 3% below the average for the five years ending 2018, when demand was similar to projected levels for this year. Moreover, looking back at the past nine winters, the maximum drawdown on storage was 773 terawatt-hours in 2018/19.

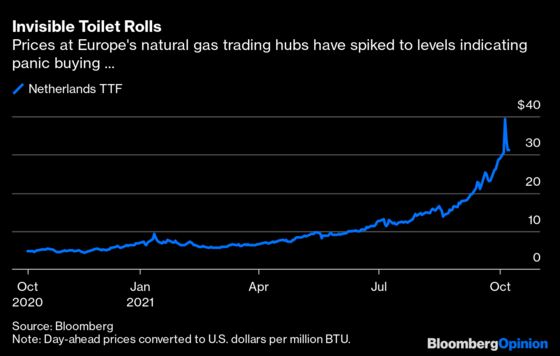

So these numbers point to elevated prices, definitely. But on their own, they don’t suggest Europe will run out of gas, which is the implication of the recent spike in prices prior to this week’s partial pullback.

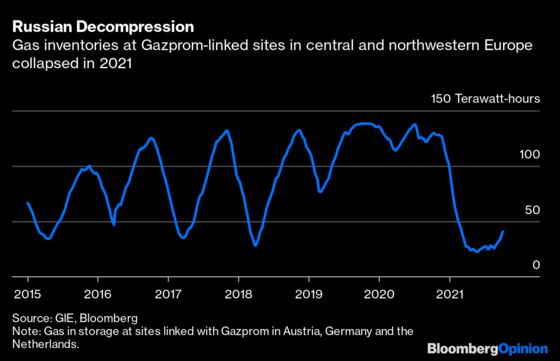

Beneath the headline storage numbers, though, there’s a gaping hole stretching from the North Sea to the Alpine valleys. Inventory in the Netherlands, Germany and Austria is below the average for the continent, ranging from just 55% full in Austria to slightly less than 70% in Germany. These three countries not only host roughly half of Europe’s entire capacity, they are strategically located right at the center of the system, providing de facto capacity for areas around them such as the U.K. and Eastern and Southern Europe.

In a pinch — a particularly cold week combined with low wind power, say — you need volume, but you also need flexibility on a gas system; the ability to quickly move molecules to where they are needed. Without that, you get regional price spikes, such as often happens in northeastern U.S. cities during the winter, or outright shortages. Moreover, as gas inventories run down, pressure in storage sites drops, making it harder to quickly ramp up withdrawals, compounding the problem.

One interesting wrinkle about those low inventories across central Europe is that facilities linked to Russian behemoth Gazprom PJSC have been particularly depleted this year.

There are perfectly reasonable explanations for this. As elsewhere, Russia is rebuilding its own gas inventory after the depredations of Covid-19, last winter’s heavy demand and the summer’s too.

But the coincidence of a hole at the strategic heart of Europe, just as Moscow is pushing to open the contentious Nord Stream 2 pipeline and seeking more long-term supply contracts for Gazprom, is tough to ignore. Given the Kremlin’s current occupant has used the gas weapon before and has a predilection for such old world pursuits as imprisoning domestic opponents and invading neighbors, the realm of possibilities here has a large footprint.

The head of the International Energy Agency, Fatih Birol, claims Russia could push more gas Europe’s way if it wanted to. Recent comments from Russian officials also suggest this, although they may simply reflect the impending wind-down of the country’s own gas injections. In any case, there’s no gas flowing west until additional volumes are actually booked on Gazprom’s pipelines.

While Russian machinations may well play a role, though, Europe needs to confront the internal weaknesses that leave it vulnerable to such things. Even if the headline storage numbers look tight but not disastrous, the system they serve has changed in ways that undermine such confidence.

For one thing, demand this year is projected to be similar to 2018, but declining domestic supply means Europe’s requirement for gas imports is higher by almost a fifth. Ukraine’s gas inventories are heavily depleted, turning a historical source of extra supply into a potential drain. Meanwhile, as with markets such as California, decarbonization of the power grid has increased the value of gas as a backup for renewable energy, even as Europe’s heating systems also compete for supply.

Europe’s position has weakened in other respects, too, such as the winding-down of the Netherlands’ giant Groningen field due to seismic activity, the closure of Germany’s nuclear-power fleet and, in the U.K., the decision in 2017 to close the country’s only major gas-storage facility.

All this has left Europe with less flexibility when faced with challenges, whether natural or man-made. More coordinated, mutually supportive gas stocks requirements, along the lines of the IEA system for oil, could help. But gas storage is much more difficult than for oil and would still leave some countries dependent on the goodwill of their neighbors. Moreover, building new storage for gas is difficult in economic and political terms given decarbonization objectives; although such facilities could potentially be repurposed down the line for hydrogen or carbon capture.

A mild winter should see Europe scrape through for now with prices dropping. A hard winter will likely mean drawing down most of what’s in storage, along with regional shortages and further price spikes. The biggest challenge of all, though, would be sudden cold snaps, testing a system that may have the gas but not necessarily where and when it is needed.

European natural gas demand was 536 billion cubic meters (51.9 billion cubic feet per day) in 2018 and is projected to be 545 billion cubic meters (52.7 bcf per day) in 2021 (source: International Energy Agency).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.