Brazilians Are Spending More Than Half Their Income on Debt Payments

Brazilians Are Spending More Than Half Their Income on Debt Payments

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Finance professor Claudia Yoshinaga asked her foreign students at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo to guess the average interest rate Brazilian credit card issuers charge on unpaid balances. She instructed them to guess high. “Their wildest bet was 50%,” she says.

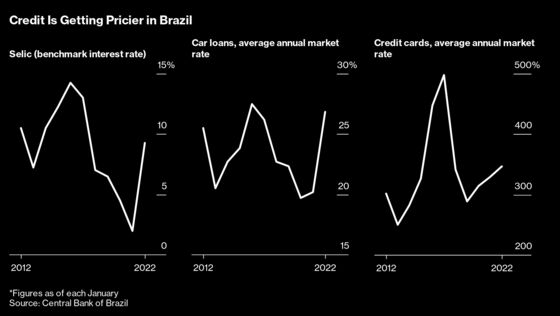

The correct answer: 346.3%. “I have students from the U.S., Belgium, Africa … and it’s unbelievable to them,” Yoshinaga says.

Brazilians who took on debt during the pandemic are bearing the brunt of the central bank’s campaign to tame stubborn double-digit inflation. While policymakers in the U.S. and Europe dithered, monetary authorities in Latin America’s biggest economy were quick to respond to surging prices, prodded by memories of bouts of hyperinflation that stretched into the early 1990s.

Since March 2021, Brazil’s central bank has ratcheted up its benchmark interest rate, called the Selic, a total of 875 basis points. The strong medicine is starting to show results. Consumer prices rose 10.4% in January from a year earlier, an improvement on an 18-year high of almost 11% in November.

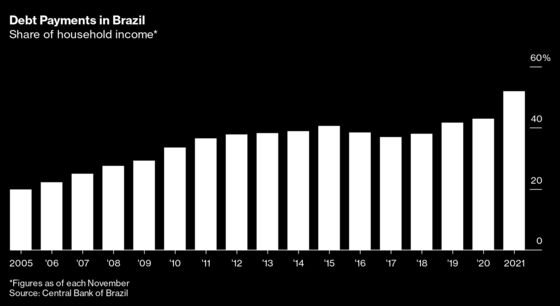

The higher rates are cutting into Brazilians’ spending power. Payments on consumer debt including mortgages, car loans, credit cards, and other types of revolving credit now gobble up about 52% of household income—a 9-percentage-point jump from 2020 and the highest rate recorded since the central bank began tracking the metric 17 years ago.

During the pandemic, more out-of-work or underemployed Brazilians began relying on credit cards or store cards to pay for such essentials as groceries and drugs. Alexandra Silva, 26, was working as a theater lighting specialist on the tourist island of Florianópolis when the crisis hit. She lost her job, and as she hustled for replacement gigs, she watched her income drop from 3,500 reais per month ($700) to 1,800. “I’m making a huge effort to not lose control over my finances. But I can’t seem to stop using my credit cards,” says Silva, who sometimes transfers balances from one card to another to give her more time to pay off charges.

When Brazil’s central bank slashed the policy rate to 2% in August 2020 to support the economy during the Covid-19 crisis, many Brazilians jumped at the opportunity to sign up for credit cards or take out loans. A host of financial technology companies competed with banks to sign up new customers. By the end of 2020 there were 134 million active credit cards in circulation, according to the latest data available from the central bank, a 35% increase from 2018.

While studying business administration in college in Rio de Janeiro state in 2017, Nathalia Rodrigues accepted a part-time job at a shoe store, persuading customers lined up at registers to sign up for a store credit card. Before long, she says, she was filled with guilt that she was helping people go into debt.

So Rodrigues, 23, transformed herself into a personal finance guru who dispenses advice on Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok on everything from how to draw up (and stick to) a household budget to how to deal with an inheritance. Her social media followers number half a million.

“As soon as they are 18, Brazilians hear from their parents that they need to get a credit card even when they have no money to pay for it,” Rodrigues says. “I’m not saying that someone who has a low income can’t have a credit card, but it needs to be granted in line with income.” The problem, she says, is that spending limits are often set too high, making it easier for novice cardholders to fall behind on payments.

Many Brazilians also took advantage of a three-and-a-half-year streak of single-digit interest rates, the longest in Brazil’s history, to buy a home. But because almost all mortgages in the country carry variable rates, many weren’t able to keep up with payments once the central bank began hiking. Brazil’s banking federation, known as Febraban, estimates that 18.7 million home loan contracts have been renegotiated since the beginning of the pandemic, though the data doesn’t differentiate between borrowers who are in financial straits and those simply looking to lock in a lower rate.

Garben Hellen, 53, a public servant in Brasília, received the keys to her newly built home only in May, but she’s already straining to afford the 1,005-reais-a-month mortgage payment, which has increased more than 10%. “If this keeps getting costlier each month, I just won’t be able to pay it,” she says.

Central bank chief Roberto Campos Neto has dismissed concerns that loan defaults will shoot up from the current low single digits, compromising the health of the banking system and the economy at large. “Credit volumes are still growing in a healthy way,” he said at an online forum last month. “Obviously we are always worried about higher indebtedness, but so far we haven’t seen anything outside of what we expected.”

Data compiled by the World Bank show that Brazil’s interest-rate spread—the difference between the average bank lending rate and the deposit rate—was the third-highest globally, at 26.8%, in 2020, the latest available year. Banks have argued the large differential is a reflection of the fact that many Brazilians lack a credit history that lenders can access to gauge their risk. Legislation that would cap interest rates on credit cards has stalled in Congress.

Rising interest rates helped tip Brazil into recession last year, and while the economy managed to eke out growth of 0.5% in the final quarter of 2021, tighter credit conditions will continue to act as a drag on the expansion. Economists are penciling in at least two more rate hikes in 2022, lifting the Selic to 12.25%.

Worsening household debt levels “will hold down activity,” says Cristiano Souza, an economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co., who predicts Brazil’s economy will register no growth for the year as a whole. “It’s part of a negative scenario of higher interest rates which dampen consumption, high inflation that erodes purchasing power, and a lack of real wage increases, which also holds back consumption,” he says.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.