A Fight to Die

A Fight to Die

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- There’s a nursery rhyme adapted from a Shel Silverstein poem that Sandy Morris used to sing at Girl Scout camp in California. It’s about being eaten by a boa constrictor, beginning with the toes, and Morris can still recite the lyrics by heart: “Oh, fiddle, it’s up to my middle / Oh, heck, it’s up to my neck / Oh, dread, it’s upmmmmmmmmmmffffffffff …”

This feeling of getting swallowed, in slow motion, is what Morris says it’s like to have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Since doctors diagnosed her with the incurable neurodegenerative condition on Jan. 6, 2018—but really before that, since she’s the type to have already done the research to diagnose herself—Morris has gone to sleep each night knowing she’ll awake with less physical function and independence than the day before.

Listen to this story

Now 55, Morris remains as mentally sharp as during her 28-year career in business management and analytics at Hewlett-Packard. Recently, she’s become a bulldog activist for people with her illness, pushing to make clinical trials more humane and expand access to experimental ALS therapies. But four years after her foot first fumbled in her horse’s stirrup, the serpent has nearly swallowed her whole. No more riding, no more cross-country skiing or trail runs through Tahoe National Forest. She now spends most of her day in bed, inanimate below the chin.

On the overcast October day I visited her home in the mountain town of Sierraville, Calif., an aide named Katherine wiped Morris’s face with a hot, wet washcloth and brushed her teeth. Another, Hannah, typed a text message to her husband, gauging his preference between chicken tacos and a burrito for Mexican takeout that night. An artificial-intelligence-powered computer screen called a Tobii tracked the gaze of her eyeballs to sift through her email inbox. A ventilator forced air up her nostrils so she could breathe. And when it was time to sit up to be fed guacamole-topped nachos and sips of a whiskey cocktail through a straw, her three adult children performed an elaborate choreography to transfer her limp body into a motorized wheelchair, with her youngest son bearing her weight on his back.

Morris is warm and intense, with creamy skin, curly light brown hair, and a dark sense of humor. She refers to herself as a shrunken head and talks about her impending death as casually and openly as if she were asking someone at the dinner table to pass the butter. She intends to use California’s aid-in-dying law, which allows mentally competent people with a terminal illness and a six-month prognosis the ability to obtain a prescription for lethal drugs. (Opponents still call this physician-assisted suicide; practitioners prefer medical aid in dying, or MAID.) She’s fulfilled all the requirements to qualify, and her case embodies the spirit of the law’s aim: to offer agency and autonomy at the end of life in lieu of suffering, indignity, and shame.

The question now: when? Surely the answer has rarely come easy for those who’ve tread this path before. How do you—how can you—know when it’s time to go? But Morris’s dilemma is complicated by a peculiar feature of America’s aid-in-dying laws: a requirement that patients “self-administer” the drugs. It was conceived decades ago as a well-intentioned attempt to ensure complete consent by mandating that the patient take the final action, a safeguard to prevent the practice from being used to euthanize vulnerable people. But in cases of extreme physical disability, the safeguard can be a barrier. It can exclude people with ALS, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions who otherwise qualify for aid in dying but have lost the ability to swallow or use their arms and hands. Patients such as these need assistance with virtually everything; the only thing they can’t get help with is ingesting the aid-in-dying drugs.

The threat of felony charges acts as enough of a deterrent for any physician or loved one tempted to help. And so that leaves Morris with a choice: She can ingest the lethal medication while still physically able to do so, as the law requires, but before she’s emotionally ready to leave her husband, their three kids, and her ALS advocacy. Or she can wait and risk losing the ability to act on her own, and thus her access to the law—and let nature take its course with a drawn-out death-by-suffocation she’s desperate to avoid.

When I first learned of Morris from her aid-in-dying physician, Lonny Shavelson, my bones ached with recognition. I immediately thought of my late father, Ron Deprez. As I wrote in Bloomberg Businessweek earlier this year, I’d helped him become one of the first people to use Maine’s then-brand-new MAID law, in April 2020. Like Morris, he’d had ALS and faced a version of her dilemma.

Morris has a thing for quotes. They adorn wall art in her home, ornaments on her Christmas tree, and posts on her social media feeds. Her favorite: “What you allow is what will continue.” When Shavelson asked if she’d want to join him and fight for the death she wants but California law prevents, she responded, “I don’t know where I’ll find the time. But I absolutely do.”

And so, in her final days, Morris has taken up another cause: to expand access to aid in dying. She and Shavelson, who’s helped more than 200 Californians make use of MAID, are the lead plaintiffs in a lawsuit arguing that the state’s aid-in-dying law violates the equal-access provisions of the Americans With Disabilities Act. The prohibition on assistance is discriminatory, the suit contends, because it either excludes the severely disabled from participation or forces them to act earlier than they would if they had assistance, thereby creating an underclass of patients denied the same right provided to the more-able-bodied.

Morris and Shavelson hope to rectify a mismatch between what the law allows and what his bedside experience shows some patients need. Medicine has evolved, they argue; laws should too. Their proposed solution would benefit only a fraction of the already small number of people who rely on MAID laws. But would it legalize active euthanasia? That’s an issue fraught with moral and ethical implications that many in the right-to-die movement have long sought to avoid.

In the early 1990s only two countries in the world, the Netherlands and Switzerland, permitted people to seek assistance from a doctor to intentionally hasten death. Efforts in Washington state and California asked voters to legalize voluntary active euthanasia—benevolently causing the death of a competent, consenting adult, usually by lethal injection. Both measures failed. It didn’t help that many physicians argued that helping people die was antithetical to their role as healers. Nor that, around this time, a pathologist in Michigan named Jack Kevorkian was starting his controversial crusade to help terminally ill people use his hand-built contraptions to end their life.

By the time the movement notched its first victory, in 1994 in Oregon, advocates had significantly narrowed their vision. The Oregon law legalized MAID but not euthanasia by requiring that the patient, not the doctor, administer the life-ending drugs. Advocates also padded the law with safeguards intended to alleviate fears that the poor, disabled, and otherwise marginalized might be coerced into ending their lives early.

Aid in dying is now legal in 10 states and Washington, D.C. Virtually all have modeled their laws after Oregon’s. Advocacy groups have been careful not to push for much more, lest they risk losing what progress they’ve made, and have danced delicately around the topic of euthanasia, as in mostly not mentioning it, and when they do, opposing it.

“Euthanasia,” which is derived from the Greek words meaning “good death,” still carries the stigma of its association with eugenics and genocide in Nazi Germany. Yet when Americans are polled on whether doctors should be able to end the life of terminally ill patients if they or their families request it, a majority has, for decades, said yes. Still, no state has passed laws allowing that. So the legal system continues to equate euthanasia with homicide or murder, even if someone consents or requests to die to alleviate pain and suffering. (As the Tennessee Supreme Court stated in 1907, “Murder is no less murder because the homicide is committed at the desire of the victim.”) That’s why Kevorkian was charged with and convicted of second-degree murder in the 1998 death of Thomas Youk, a former race car driver with ALS. By then, Kevorkian had supplied the means to die to about 130 people (and avoided prison); Youk’s was the first case in which he took the final action, by administering a lethal injection. He then gave a videotape of the act to CBS to air on television, which is how the world learned what he’d done. He tried to defend himself on the grounds that Youk’s death constituted a mercy killing. But as the Michigan Court of Appeals explained, in declining to overturn his conviction in 2001, “consent and euthanasia are not recognized defenses to murder.”

“If you don’t have liberty and self-determination, you got nothing,” Kevorkian told CBS before spending eight years in prison. “This is the ultimate self-determination: to determine when and how you’re gonna die when you’re suffering.” Disability rights groups have figured prominently among opponents. Sanctioning active voluntary euthanasia, they argue, risks too easily slipping down the slope of putting patients to death even when they don’t or can’t consent.

All or parts of a dozen countries permit aid in dying. Most allow voluntary active euthanasia. Many in the U.S. MAID movement now quietly cite Canada as an ideal model. There, people can opt to either ingest aid-in-dying drugs themselves or have a physician administer an injection, the most clinically efficient route to death. Of the 21,589 people who’ve participated since legalization in 2016, fewer than 1% have chosen to self-administer. (The U.S. total is far less: Fewer than 4,500 since 1998, according to data compiled in January by advocacy group Death with Dignity National Center. Users tend to be White, educated, and insured.)

“I need to warn you that there is not much left of me,” Morris told me in an email prior to my visit in October. All she could move below the chin were three fingers. That meant her ALS had long since progressed far past my dad’s.

Grief had taken me down some strange paths in the year and a half since I’d held my dad’s hand as he died. I’d become obsessed with figuring out how his story fit into the evolution of aid in dying. Confronting it all so directly had been cathartic but also emotionally draining. And there I was, pulling into Morris’s gravel driveway in the mountains, reliving it all again.

I feared entering the depressing sick house of a plaintiff in an inherently sad lawsuit about death and disease. But as soon as I walked inside, I saw a hive buzzing with love and purpose and a family devoted to doing whatever it took to keep Morris happy and alive. She’d participated in a yearlong clinical trial for an experimental stem cell therapy in San Francisco. When the trial ended, she and her husband of 28 years, Joe, made the 20-hour journey to South Korea four times to continue similar treatments.

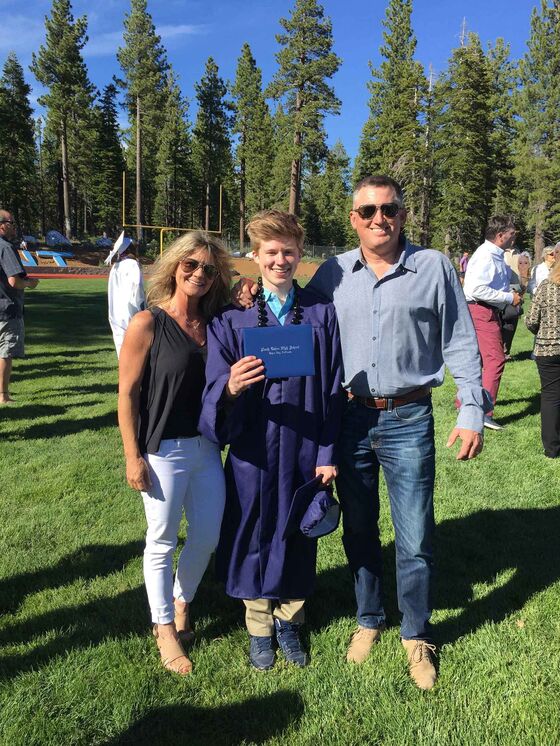

At a time in life when young adults tend to yearn for independence, 20-year-old son Justin and 24-year-old daughter Kylan have made the extraordinary sacrifice to be their mother’s primary caregivers, with all the messy, intimate work that entails. The family got spooked after two friends with ALS on ventilators died overnight, so now Justin camps out on a cot next to their parents’ bed to respond at a moment’s notice, and Kylan provides backup on a couch nearby. Joe runs the family’s construction company with another son, Colton, who’s 22. Morris’s parents stay over part time to help with household chores. All three kids have traveled to lobby lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

Morris had given detailed instructions to “Sandy’s squad,” as she calls her care team of family members and hired aides, to bake cookies for my arrival and lay out a spread of coffee, pastries, and fruit. “Life is short,” she said, urging me to eat. She was full of energy and never stopped talking, despite the difficulty. She had five conference calls, with U.S. senators, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and others, within the span of a few hours, determined to accomplish more, more, more, not wallow in misery over all that had been lost. She seemed to accept her reality, not out of resignation but as a way to be free to move forward. On the precipice of death, she was more alive than most people I’d ever met.

Morris’s mother had found her doctor, Shavelson, through a friend. A former emergency-room and primary-care physician, he opened in 2016 one of the first U.S. practices focused solely on aid in dying. He charged a flat fee of $3,000 for as much consulting as people wished. Like Morris, he is direct, shunning euphemisms such as “pass away.” In what he calls the how-you-die conversation, he tells people, “This is what suffocation looks like, this is what dehydration looks like, this is what kidney failure looks like.” What’s scariest of all is the unknown.

In 2020, Shavelson co-founded and now leads the American Clinicians Academy on Medical Aid in Dying. Its goal is to make the still nascent and stigmatized field of assisted death more sophisticated, guided by best practices, especially in places where experience and knowledge are thin. For too long, Shavelson says, too many doctors wrote prescriptions and left patients alone to decide when to die. But good aid-in-dying care is about listening to what’s bothering people and seeing what can be fixed. “The day of aid in dying is easy,” he says. “It’s getting people to that day.” He recalls one patient whose extreme exhaustion was fueling his desire to die. Shavelson learned he was waking at night multiple times to urinate and recommended a catheter, and the man lived another four months. “I spend much more of my time adding time to somebody’s life than taking it away.”

Shavelson stopped taking on new patients last year. By then he’d watched helplessly as dozens lost access to California’s law because of severe disability. While drafting an article about the issue for a bioethics journal, an idea struck: Why not look to the legal system for a fix?

Morris had been Shavelson’s patient for more than a year. She’d shared with him her passion for activism, and he’d come under the spell of her magnetism. It helped that Shavelson isn’t only a doctor but a journalist, too. He’s produced audio segments for NPR and video documentaries and has written books, including A Chosen Death, about the underground world of assisted dying, published in 1995. He recognized the importance of identifying a compelling and sympathetic character through which to tell a narrative and surmised that might also benefit a court case.

Kathryn Tucker, an attorney whom he’d met years prior, agreed. Tucker had long been in the trenches on issues central to the case, having served as director of advocacy and legal affairs at Compassion & Choices, a leading MAID group, and later as executive director of the Disability Rights Legal Center in Los Angeles. It had been Tucker’s idea to pursue what became Washington v. Glucksberg, one of the few right-to-die cases to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. As lead counsel to a group of doctors and terminally ill patients, she argued that they had a constitutional right to what was then called physician-assisted suicide. In 1997 the justices disagreed and cited the slippery slope argument but left states to decide the matter for themselves.

One year later an elderly woman with cancer became the first person to use Oregon’s MAID law. Peter Reagan, a family medicine doctor in Portland, prescribed her a massive dose of the sleep aid Seconal. A helper mixed the powder inside the capsules with liquid, which she then swallowed herself. For years, all MAID deaths followed that script. The bright line between MAID and euthanasia remained. Doctors recognized that for certain patients it might pose problems, Reagan tells me, but “we weren’t trying to solve them. It was hard enough work to just do it for the people who obviously qualified.”

Protocols and standards of care have since evolved. Shavelson is a new, rare breed of doctor whose sole focus is aid in dying. He helped develop the current drug standard: a massive dose of sedatives and anti-anxiety medications more efficient at painlessly stopping a human heart. He and his colleagues have also found new ways to deliver them. For those who can no longer swallow, the lethal cocktail can be loaded into a feeding tube or rectal catheter, which the patient then administers by pushing a plunger. Those lacking arm or hand strength can sip the liquid with a straw. States have also begun revising their laws.

Such developments have expanded MAID access to some patients who’d have been previously excluded, but it still leaves out people who can neither swallow nor use their arms or hands. In other words, people like Morris if she lets her ALS progress much further. The changes have also led to the potential for some previously unfathomable complications: What if a patient starts to depress a plunger full of enough medication to end their life but then runs out of strength partway, unable to finish the task?

The lawsuit proposes letting a patient such as Morris get help administering the drugs when she no longer has the physical capacity to act exclusively on her own. If she and a helper both push down a plunger connected to a feeding tube and thus together cause her death, is that MAID or euthanasia? When does any amount of assistance cross the line?

“Conceptually it gets really messy,” says Thaddeus Pope, a law professor and bioethicist who has written extensively about MAID and has advised Shavelson. “The vocabulary that we have both in the law and the medical and ethics literature is usually framed around 100% clinician or 100% patient. No one has focused on this mixed situation, so I don’t know what to call it.”

In 2015, California lawmakers proposed an aid-in-dying bill that looked a lot like Oregon’s. But the final version included an extra safeguard, spelling out that a person may “assist the qualified individual by preparing the aid-in-dying drug so long as the person does not assist the qualified person in ingesting” it. Although no other MAID law includes such explicit language, the medical community has generally interpreted the self-administration requirement as enough to foreclose the possibility of assisting. California’s law leaves no room for an alternative interpretation. Then-state Senator Bill Monning, a chief sponsor of the law, tells me it was a necessary political concession, without which the bill wouldn’t have passed.

That’s the part of California’s law that Morris and Shavelson’s lawsuit specifically challenges, on behalf of all people with terminal illness that causes progressive physical disability and the physicians who treat them. Such patients, the suit says, either can’t self-administer aid-in-dying drugs without assistance or can’t do so “at the time they wish.” That violates the ADA, it says, one of the country’s most comprehensive civil rights laws, passed in 1990 to ensure “people with disabilities have the same opportunities as everyone else to participate in the mainstream of American life.” The lawsuit seeks “a limited exception” to the prohibition on assisting with ingestion, with a goal to “amplify, when possible, the patient’s own physical abilities.”

The suit names as a defendant California Attorney General Rob Bonta, who’s responsible for prosecuting anyone who violates the MAID law. In his initial opposition, he called the request for ingestion assistance an “extraordinary remedy” that would constitute a “fundamental alteration” of the law. “It would sanction the use of ‘active’ euthanasia,” he wrote, “which is expressly barred under Penal Code Section 401.”

That logic appears to have resonated for now with the U.S. district judge assigned to the case, Vince Chhabria. The initial complaint, filed on Aug. 27, sought emergency relief to allow Morris and a fellow plaintiff, a 75-year-old woman with advanced multiple sclerosis, to get assistance with ingestion as the case made its way through court. Chhabria denied that request in an order on Sept. 20. “The line between assisted suicide and euthanasia is a significant one,” he wrote, using the outdated term for MAID that’s still preferred by its opponents. “It is unlikely that the ADA could be reasonably construed as requiring a state to cross the line to euthanasia merely because the state has chosen to authorize assisted suicide.” The next day, the woman with MS ingested the MAID drugs and died. The case is moving forward.

California’s requirement that people self-administer without assistance, Chhabria wrote, was reflective of “a legislative judgment that no person’s life should be ended unless they are fully committed to ending it—something that may never be truly clear unless they actually perform the act.” This is the part that leaves Morris especially exasperated. She lists some of the law’s other guardrails to ensure voluntary participation: “I have already signed, and my doctor and a second doctor have already signed, a form saying, ‘Sandy wants to die when she’s ready because she’s within six months of her death and it’s fair that she chooses.’ And then I waited two weeks, and we all signed again to say, ‘Yep, Sandy is not compulsive. She really wants to do this.’ So why in the f---, why are you questioning the process when I’ve already told you I want to die? Nobody is trying to kill me. I’ve already said I want to die.” (She’s even arranged for her brain to be shipped to ALS researchers in Boston.)

For Shavelson the requirement is “singularly without precedent” in health care: “Patients sign informed consent forms for everything from heart transplants to brain surgery. Yet no surgeon says, ‘to be sure you’re fully consenting, here’s the scalpel, please make the first cut.’ ”

Prior to my dad’s death, on April 21, 2020, only one other Mainer had qualified for MAID. Local advocates had offered us conservative guidance: My brother and I could prepare the drugs for Dad, but he’d need to hold the cup to drink them on his own. He’d lost the use of his right arm by then, and the left was not far behind. Morris and Shavelson’s lawsuit left me ruminating about my dad’s fear of losing access to the law and how it had influenced his decision about when to die.

After visiting Morris and her family in Sierraville, I examined Maine’s MAID law more carefully. Its definition of self-administration struck me as awfully vague: “to voluntarily ingest.” Can’t you do something voluntarily and get help at the same time?

The bill’s chief sponsor, a neurologist and state representative named Patricia Hymanson, didn’t dispute my interpretation. The ambiguity wasn’t an oversight, she told me: “We wanted it to be as simple as it could be in order to allow people to make decisions with their one death.” But how would you know when you’ve crossed the line, I asked, if the line isn’t well-defined? “I don’t have a good answer for you,” she said. “These questions are being answered patient by patient, and I trust the medical community to do the right things. I trust the medical community more than a black-and-white law that’s engraved in a law book. I trust the ambiguity more.”

I called Shavelson from the makeshift office at my dad’s house where I’ve been staying with my family. I could see my dad’s truck in the driveway through the window, and I was wearing his old blue geometric-print fleece jacket. It was 18 months to the day since his last.

Most people using MAID have cancer and never lose the ability to self-administer. Cancer’s end stage tends to announce itself, Shavelson explained, signaling it’s time to take the MAID drugs to avoid potentially painful final days. Neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS, however, progress slowly and gradually. Patients lose the ability to self-administer without assistance, but it’s hard to pinpoint when.

According to the now-common interpretation of the laws, I could have held the cup as my dad drank the lethal liquid with a straw. (Pouring it down his throat, meanwhile, is still thought to be going too far.) It didn’t feel healthy or rational to wish I could go back and change my dad’s death, I told Shavelson. But I couldn’t help but rue its timing. My dad used Maine’s law when it was new, before people here had experience or time to fully understand what it did and didn’t allow. How much of his life, as a result, got cut short? He wouldn’t have wanted to last months more. But days or weeks? Perhaps.

You can’t dwell on regret in medicine, Shavelson responded. “The death rate from the 1918 flu would have been much less if we’d had ventilators, but we didn’t. And that’s the way it goes.” It’s not only medical technology that evolves. Standards of care, along with our understanding of what’s possible and what’s needed, do, too. “Medical aid in dying is a new field in medicine, and it’s taken some time to get these best practices established,” Shavelson said. “I’m sorry your dad wasn’t around for when things were improving.”

Sandy Morris understands all that. She’s not urging Congress to expand access to experimental ALS therapies because she thinks she’ll live long enough to receive such treatment herself. Nor has she taken on the added burden of her and Shavelson’s lawsuit expecting to benefit from any changes to California’s MAID law it may one day yield. She’s doing all this with one aim in mind: to make the path smoother and more hopeful for others like her in the future. These fights give her purpose. Without them she’d already be dead.

For now, Morris is determined to ingest the lethal drugs on her own while she still can. Her wish is to survive until at least New Year’s Eve; her family is planning a party. Then she’ll die, when it’s time, on her porch with her loved ones around her and a whiskey cocktail on hand, overlooking the forest and valley below. “I would never leave this beautiful life early,” she says. “But ALS demands it.”

Read next: How I Helped My Dad Die

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.