Buyout Giants Offer Perks to Lure Investors in Most Competitive Market in Years

Buyout Giants Offer Perks to Lure Investors in Most Competitive Market in Years

(Bloomberg) -- The biggest names in private equity are deploying new tactics to elbow out rivals during the most frenzied race for investor cash in years.

Blackstone Inc. is offering early-bird discounts, even to late arrivals. Apollo Global Management Inc. is redoubling efforts to put its CEO in front of pension funds while pitching its next flagship investment vehicle. Others say it’s now harder to raise money as roaring inflation, rising rates and the war in Ukraine have brought the prolonged era of easy fundraising to an abrupt end.

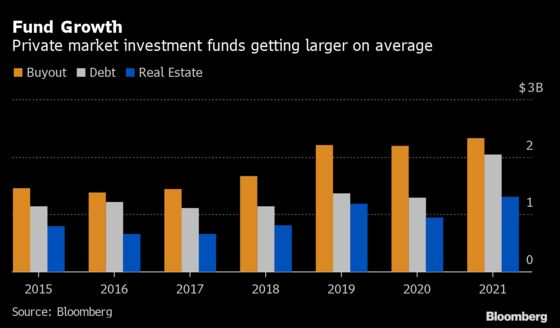

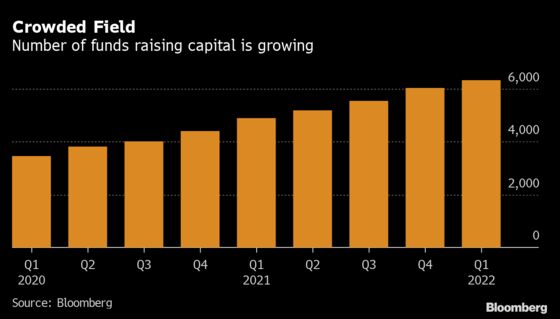

The headiest of days in the buyout world had lured more firms than ever to set record targets for their latest funds. They’re confronting the most competitive market in years, and pulling out more sales incentives as the challenges mount.

“Investors are very spoiled for choice right now,” said Andrea Auerbach, head of private investments at Cambridge Associates.

Many money managers are rushing out new funds before markets deteriorate further, she said.

“The music might stop and we could be at the very end of musical chairs,” Auerbach said. “So everyone walks around faster and faster.”

Buyout firms are currently seeking $488 billion, 41% more than in 2018, according to data from Preqin. But many are discovering that pension funds have too many options and not enough money to go around.

Blackstone, which is targeting about $25 billion for its next flagship buyout fund, is giving investors the option of splitting their commitments between the initial phase of fundraising, known as a “first close,” and a 2023 deadline, according to people familiar with the matter. While private equity firms sometimes offer early-bird discounts to investors that commit to the first close, Blackstone is now offering to give the entire fee break to those who split their commitments between closes.

A respectable first close telegraphs to the market how much cash firms have on hand and when they can start making deals.

Apollo, led by Chief Executive Officer Marc Rowan, has signaled it intends to close this year on its latest flagship vehicle, targeting $25 billion, and do so in one fell swoop. But executives have told some prospective investors they could wait until 2023 to commit, roughly a year after it started marketing the fund, people familiar with the matter said. Five years ago, it took Apollo roughly six months to raise the same amount.

The slowdown follows last year’s departure of Rowan’s predecessor and fellow founder, Leon Black, whose business ties with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein threatened fundraising as investors weighed the reputational risks of doing business with New York-based Apollo.

Rowan’s team has said the controversy is behind the firm for good, and Apollo has publicly touted its fundraising progress, with Co-President Jim Zelter telling analysts in February that he was confident about hitting the target.

TPG, meanwhile, is offering to accept 2023 commitments for its flagship vehicle and a health-care pool as it seeks a combined $18.5 billion, people familiar with the matter said. Clayton Dubilier & Rice and Accel-KKR, which aren’t in the market yet, have also offered to be flexible, other people said. All of the firms declined to comment.

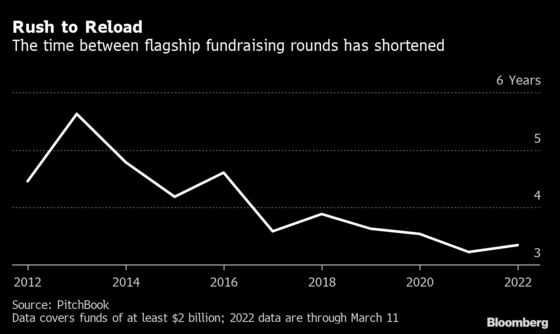

In the past decade, rock-bottom interest rates prompted yield-starved investors to pile into private equity with an appetite so insatiable that it encouraged buyout firms to return to the market as rapidly as possible -- and with ever-bigger fundraising goals. By 2021, it was taking just three years since a previous fund closing for a firm to raise its next one, the quickest turnaround since 2009, according to PitchBook data.

The industry became a victim of its own success. With equity markets chugging steadily higher -- at least through the start of this year -- assets swelled, fattening the private equity holdings of pensions and endowments. Now many of those same institutional investors have maxed out what they’re able to invest in buyout and venture-capital firms.

‘They’re Stuck’

Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis compounded those challenges, leading to a so-called denominator effect, with falling stock prices helping to inflate portfolios’ relative exposure to private equity. That means they’re more cautious about locking up even more cash in hard-to-sell assets.

“Investors are sitting here saying, ‘I have 10 managers coming back when I expected to have six or seven, but I don’t have room anymore,’” said Kelly DePonte, a managing director at Probitas Partners, which helps raise money for private equity funds. “They’re stuck.”

For the fiscal year ended in June, 44% of government pensions worldwide were above their target allocation to private equity, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. One of Britain’s largest pension managers, the Universities Superannuation Scheme, is bumping up against that threshold.

“There is no way we can recommit at the same level as before,” said Geoffrey Geiger, head of private equity at USS, noting that his plan has managed to secure better returns and more co-investment opportunities because of this dynamic.

It also means that after years of being forced to stomach less favorable terms, pensions now have the upper hand in some respects.

“The pendulum has shifted in our direction,” said Scott Ramsower, head of private equity funds at the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

Some are seeking to address the constraints by selling current private equity holdings on the secondary market or boosting their target allocation to the asset class. The two biggest public pensions in the U.S. -- the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and California State Teachers’ Retirement System -- both increased their targets to 13%, up from 8% for Calpers and 11% for Calstrs.

Private equity firms, meanwhile, are hoping to tap into alternative pools of capital to bolster fundraising. But distributors such as banks, which act as intermediaries between investors and the buyout shops, are also struggling to raise money from wealthy clients who want to hang on to their cash for longer after the recent market volatility crimped their fortunes.

Signs of fundraising struggles are already emerging.

Centerbridge Partners has raised $4.5 billion between a flagship fund and co-investments, after initially seeking $6 billion, a person familiar with the matter said. The firm eventually expects to raise as much as $5 billion. Centerbridge wrapped up fundraising late last year for the main fund to focus on investing. The mixed track record of prior funds made the current one less appealing, other people said.

BC Partners, meanwhile, fell short of the 8.5 billion-euro ($8.9 billion) target for its 11th flagship fund, and Intermediate Capital Group Plc wound up about 400 million euros shy of its 1 billion-euro goal for its Recovery II Fund.

There will be a “period of natural selection” that will benefit stronger and also specialist managers, said David Layton, CEO of Swiss investment firm Partners Group Holding AG.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.